Part 1 of our Small Business Series

The following is the first in a two-part series by Julia Pollak exploring the role of small businesses in an equitable recovery.

Read Part 2: COVID-19 has been Toughest on Minority-Owned Businesses

Business dynamism and startup-creation had been falling for two decades, even before the coronavirus crisis struck. Now, the pandemic has forced tens of thousands of small businesses to shutter and one-in-five say they may have to close their doors by year’s end if current economic conditions do not improve. If too many small businesses fail and too few new ones take root, that will prolong the recession, delay the recovery, change the economy and damage U.S. towns and cities—perhaps irreparably.

The Current State of Small Businesses

Three-fifths of small-business employees stopped logging hours at the start of the coronavirus pandemic as an estimated 1.85 million businesses temporarily suspended operations. Although there has been a substantial rebound in economic activity since April, data from Affinity Solutions suggests that small business revenue is falling even as consumer spending recovers, because spending is gravitating towards larger companies.

The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) helped more than 5 million businesses to stay afloat and cover payroll costs. But the program has now expired and 84% of program beneficiaries say they have used up their loan. If there is another round of PPP funding, 44% of small businesses say they will apply for a second loan. In the meantime, more small businesses are shedding jobs than adding them, according to the Census Bureau’s most recent small business pulse survey. And it’s no surprise—22% say their sales are less than half of their pre-crisis level and half say their sales have fallen by 25% or more.

Why Small Business is so Important

Both in good times and bad, small businesses are the heart of the economy. They are responsible for a larger share of the new jobs created each year than their base share of employment, and have often boosted employment during recessions.

For example, entrepreneurship and self-employment served important roles in the gulf region’s labor market recovery after Hurricane Katrina. After that crisis, high local unemployment rates pushed people to start their own small businesses. Similarly, many workers who lost their jobs during the Great Recession responded by starting their own businesses.

Small businesses are responsible for a larger share of new jobs creation, and have often boosted employment during recessions.

Another benefit of small businesses is that they often drive innovation and competitiveness. According to one study, small firms are roughly thirteen times more innovative per employee than large firms, partly because they can make decisions quickly and reward top performers. More than half of the firms that experienced high growth in the wake of the Great Recession from 2009 to 2012 had less than 10 employees in 2009.

Small businesses also play a crucial role in expanding opportunity for workers who have traditionally faced barriers to employment. Compared with larger companies, which tend to be more bureaucratic and risk-averse, small businesses are often more open to providing job opportunities to people who face barriers to employment, such as people with criminal records. Small businesses are substantially less likely to conduct background checks, for example. They are also very often the driving force behind the development of towns and cities, employing local workers and contributing to local governments through taxes.

What Has Happened to U.S. Business Formation

Despite all the important roles small businesses serve, the U.S. appears to have become less hospitable towards them in recent years. Business dynamism and the rate at which startups are forming has been declining since around 2000. It has fallen in all fifty states, in almost every metropolitan area, and across industries.

Reversing the decline in business dynamism may not have been a policy priority during a ten-year economic expansion in which the economy added jobs despite declining new business starts. (The economy was able to add jobs thanks to job growth at existing businesses and a decline in layoffs.)

If too many small businesses fail, it will prolong the recession, change the economy and damage towns and cities—perhaps irreparably.

But when so many existing businesses are dying, it becomes more important than ever to encourage the birth of new ones. For many workers, starting a business could be an attractive alternative to competing in an anemic labor market, if only we cleared some of the obstacles.

Four Reasons U.S. Business Dynamism Has Plunged

Economists have identified several barriers that hold people back from starting small businesses:

The overuse of intellectual property protections.

One important factor has been the increased use of intellectual property protection by market leaders to limit the diffusion of knowledge to other businesses. There is considerable evidence that copyright and patents are increasingly being used by politically powerful firms to maintain monopoly profits. Of course, some intellectual property protections are necessary to incentivize innovation. But arguably, the system has been extended well beyond the point where benefits outweigh costs.

Another disturbing trend is the expansion of the use of so-called noncompete agreements, which limit workers’ ability to start their own companies in the future. More than a quarter of U.S. workers are now subject to such agreements, according to research by the Economic Policy Institute.

The decline in small business lending.

Another important factor has been the shrinking availability of credit for small businesses following the Great Recession. Small business lending by the four largest banks fell sharply in 2008 and remained depressed for many years. In counties where the largest banks had a high market share, the overall flow of credit to small businesses tumbled, interest rates rose, fewer businesses expanded, unemployment rose, and wages fell. It has taken more than a decade for smaller lenders and financial technology companies to start plugging the gap.

The decline in small business lending was partly the unintended consequence of financial regulations designed to strengthen the financial system and avoid a repeat of the Great Recession. While those are noble goals, evidence that the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and Dodd-Frank Act have hindered small business lending and restrained business formation suggest some tweaks and fixes may be overdue.

The costs of employer-sponsored health insurance.

Half of Americans receive health insurance through their employers. With the average annual cost of an employer-sponsored family plan now totaling $20,000, it’s not hard to see why the current system discourages business formation and depresses employment and wages.

It is also inequitable. When employers spend thousands on health insurance, they treat it as a fixed cost, raising the working hours of the group of workers to whom they provide health insurance while capping the hours of other workers below the threshold for eligibility. There are also perverse distributional effects that result from the tax-exempt status of employer-provided insurance. According to research using data from the Social Security Administration, workers in the bottom fifth of the income distribution receive benefits of around $500 a year while those in the top fifth receive benefits of around $4500.

If ever there were a time to break the link between employment and health insurance, it would be now—a global pandemic in which millions have lost their jobs, and with them their health coverage at the time when they need it most. Decoupling the two could reduce the costs to employers of hiring workers, boost workers’ wages, and reduce job lock—improving economic mobility and dynamism through multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

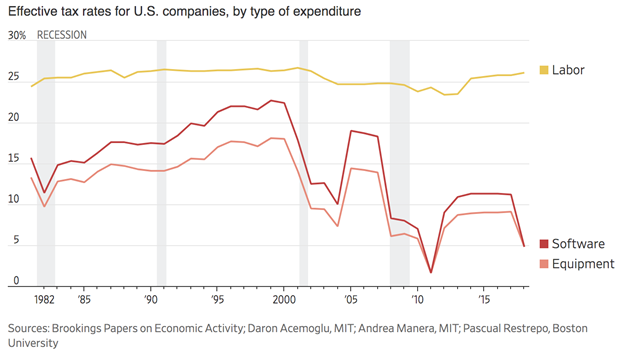

The tax code’s subsidization of automation.

Payroll and related taxes on labor have held steady over the past 40 years, but the effective tax rate on automation has fallen by more than half, according to a recent study. That means the U.S. tax code effectively subsidizes robots (or software and equipment more generally), and the companies large enough to afford them. Small businesses—especially those in the service sector—tend to spend a larger share of their revenue on wages. And that puts them at a relative disadvantage.

Opponents of reducing payroll taxes argue that the funds are needed to pay for Social Security and Medicare. But if ever there were a time to find an alternative means of funding social programs in the service of boosting small business formation and employment, it would be now. My own preference would be for governments to eliminate payroll taxes and replace them with a carbon tax. Why not use this moment to usher in the cleanest full-employment economy the world has ever seen?

We Should Focus on Improving Business Dynamism Now

Arguably, dynamism is a necessary feature of the U.S. economy. Workers spend about 4 years on average at the same job in the U.S., but about 10 years at a single job in Germany. Most Americans are at-will employees who can be fired with little notice and without cause, whereas most European workers have more protection from layoffs. The benefit of living in a place where it’s easier to get fired is that it is also easier to get hired and easier to start a business. Unemployment tends to be lower, especially for youth and minorities. But if U.S. business dynamism continues to fall, then our labor market could lose the key thing it has going for it.

The current crisis is taking place against the backdrop of a 20-year decline in business dynamism.

While the urgent priority now is helping displaced workers and struggling businesses in an unprecedented emergency, we should keep in mind that the current crisis is taking place against the backdrop of a 20-year decline in business dynamism. Fixing that problem could make the recovery swifter and more inclusive, and the economy more resilient in future.