A true reckoning with race means grappling with its generations-long emotional and economic impact

Ask any Black person in this country older than 50 about some of the formative macro-scale shifts in their lives. Many of those shifts are likely seen through the lens of race; folks may recall the Reagan administration’s brutally racist war on drugs; the videotaped beating of Rodney King and the Los Angeles Riots that followed the acquittal of his four police abusers; widespread local and federal policy that explicitly tied being Black to being a criminal; and the last decade’s steady stream of cell phone videos capturing Black men being murdered on camera—either at the hands of law enforcement or White citizens intent on taking a Black life behind the guise of a “citizen’s arrest.”

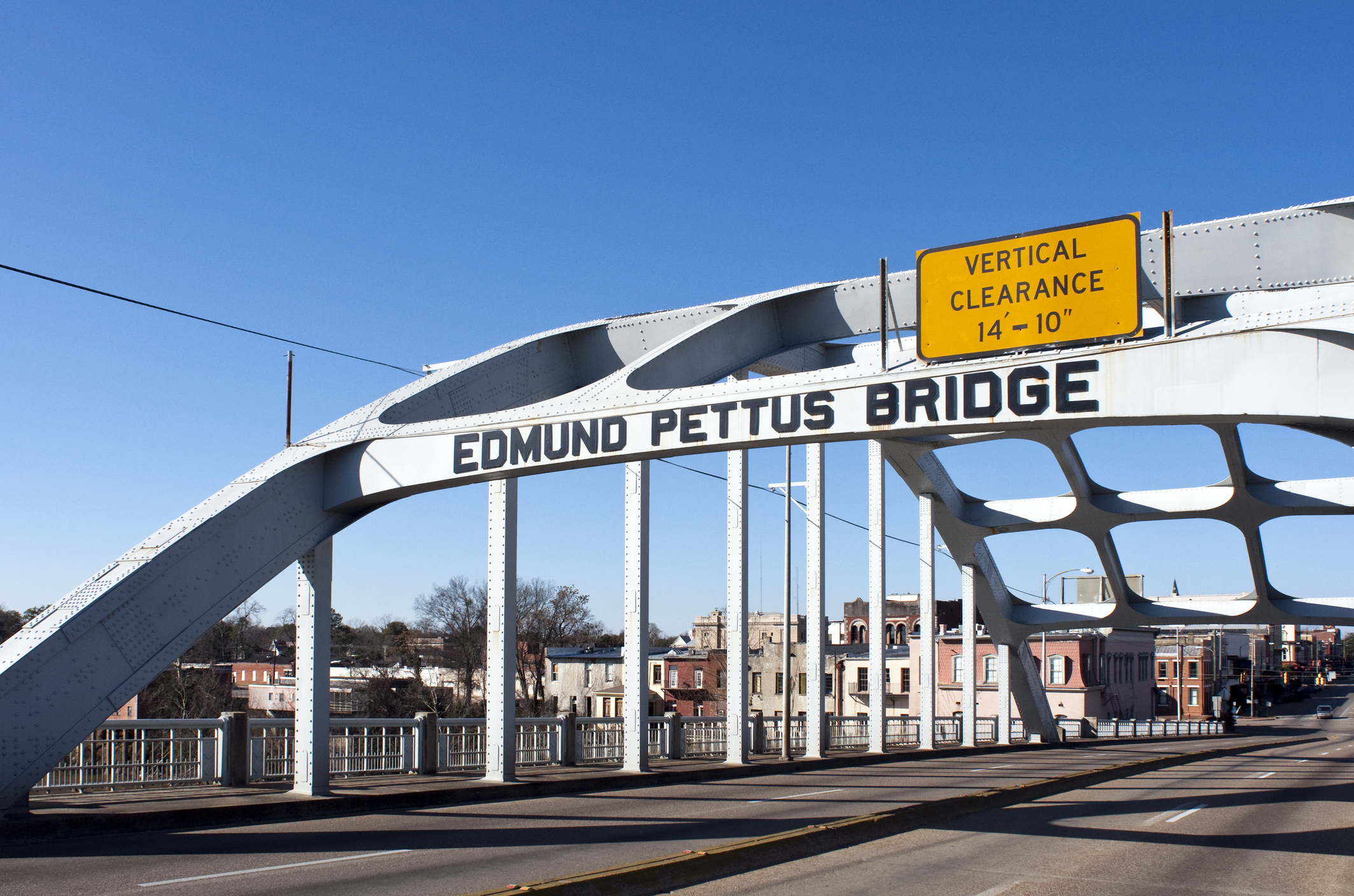

Talk to a Black American who’s a bit older, and they may recall the great atrocities of the Civil Rights Movement and the painful regularity with which they were committed. Later this summer will mark the 65th anniversary of Emmett Till’s lynching and we’re just days removed from annual remembrances of the heinous 1963 murder of Medgar Evers, which came just a few months before the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. Most Americans aged 65 or older remember the high-profile deaths of 1968, when Robert Kennedy delivered the news of Martin Luther King’s death to a crowd in Indianapolis just two months before Kennedy himself too died by an assassin’s bullet.

To be Black in America is to carry with you the collective trauma of every act of brutality against your people that came before you.

To be Black in America is to carry with you the collective trauma of every act of brutality against your people that came before you.Today’s older Black Americans remember the generations-long, frequently state-sanctioned suffering that’s taken place over their lifetimes, all of which was preceded by stories from their parents about Reconstruction, the height of Jim Crow, and abominations like the Tulsa Massacre, which thanks to pop culture is finding new relevance in the minds of White audiences.

Unprecedented Economic Disruption

That trauma has always been profound but the past few months—even before the global protests that followed George Floyd’s murder and a greater White acknowledgement of the depths of systemic racism—have added to the weight of those already burdensome memories. An unprecedented economic disruption has put millions of Americans out of work, and like so many aspects of life, it’s significantly worse for Black Americans. As seen through the lens of the still present public health crisis, the group perhaps most at risk is the very group with the most collective trauma, even before COVID-19: older Black Americans.

The disproportionate COVID-19 death toll on older Black people has been well-documented, and the economic numbers bear out these disparities, too. As the scale of global protests reached their peak during the first week of June, the Bureau of Labor Statistics revealed its May unemployment numbers. Headlines latched onto a surprise drop in overall unemployment, but for older Black workers, the news wasn’t rosy. The Black unemployment rate was four percentage points higher than the rate for Whites, and for people aged 65 and older, it was a full percentage point higher than the overall White number. It’s with those numbers in mind that many older Black Americans attempt to do the unthinkable: reconcile the unimaginable pain of their past with the perilous uncertainty of the future. And if the calls of recent weeks focused on atonement, reconciliation, and building more equitable systems are to be taken seriously, then we need to acknowledge that past and create policy that improves those future prospects.

There are efforts underway to do this. In the last couple of years, the American Psychological Association has released resources about how to support older Black adults through race-related stress, and groups like the Diverse Elders Coalition work to promote understanding of underrepresented aging communities. But we need large-scale policy change if we hope to ever start to make real economic progress for these communities. At the federal level, there’s a framework in place to prohibit racial workplace discrimination, and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act has for more than 50 years codified the illegality of discriminating against workers aged 40 or older. But these policies, and similar ones in cities and states, operate in silos, and enforcement of one transgression often comes at the expense of enforcement of another.

Policy Solutions

Many of the policy considerations in the last few weeks have rightly been focused on how to reform law enforcement, which is a logical response to the inciting incident—another killing of an unarmed Black man at the hands of police. But police reform, particularly when you consider how police encounters are much more likely among younger Black people compared to older Black Americans, should be but one meaningful step in what has to be a much longer-term, sustainable journey; among the steps that should come next are those focused on reforming workplaces—and workforces. An open letter to white corporate America from marketing executive Omar Johnson appeared earlier this week in The New York Times, calling on businesses to increase Black hiring in all parts of their organizations.

But it’s important for us to remember that the plight of many Black workers doesn’t necessarily take place in corporate workplaces, but also in retail establishments, call centers, or behind the wheels of delivery vehicles. That’s especially the case as Black Americans age, and it highlights why we need a comprehensive view of workplace reforms that takes into account the disproportionate challenges that arise when you combine race, age, and income. Until we consider the full experience of the people who’ve lived a lifetime of suppressed trauma, inequities, and death, we can’t hope to build a better future for them and the people who will follow in their footsteps.

Until we consider the full experience of the people who’ve lived a lifetime of suppressed trauma, inequities, and death, we can’t hope to build a better future for them and the people who will follow in their footsteps.