For all the bluster about the importance of swing states and swing voters, turnout and key issues, there’s a voting bloc that’s remarkably consistent in its turnout that often goes undervalued in how politicians make their pitch: older Americans. By age, people over 60 have been the group with the highest turnout in every election since data has been gathered, and only voters with graduate degrees turn out in higher numbers. And when you account for the fact that there are more than 3X as many 60+ voters as those with graduate degrees, it becomes clear that older voters are the most dependable bloc in American politics.

These voters have historically trended Republican, particularly as age rises. But as with so many aspects of the 2020 election, conventional wisdom may be flipped on its head. The reliable turnout of older Americans has the potential to be imperiled by a president intent on encouraging the suppression of mail-in votes—during a pandemic that disproportionately hurts older people who may have reasonable fears about voting in person—something that the president’s own party recognizes as a huge risk.

By age, people over 60 have been the group with the highest turnout in every election since data has been gathered.

But the “how” as to the way older Americans decide to vote isn’t the only meaningful consideration that could result in a shift. Seven months after the first of more than 205,000 Americans died as a result of COVID-19, we know far more about who is at risk for hospitalization, the means by which people can significantly decrease their risk of contracting the coronavirus, and the damage that the virus can do on both a personal level and if it overruns our hospital systems, as it has on multiple occasions since the pandemic started.

You’d be hard-pressed to square those facts with some of the rhetoric on the campaign trail, though, as the president has repeatedly downplayed the importance of COVID-19 by framing it as an issue “only” for “elderly people with heart problems and other problems.” Whether that rhetoric will move voters is anyone’s guess, as the president’s support has been remarkably resilient in the face of seemingly limitless scandals.

There are promising signs for former vice president Joe Biden; various polls show Biden leading by double digits among voters over the age of 65. Americans between 50 and 64 still favor the president by a smaller margin, but if numbers hold for the 65+ crowd, it will be the first time that a Democrat has won that group since Al Gore in 2000.

There are countless potential reasons for this year’s shift, those of which are being considered across all age groups, demographics, and cohorts. But only Biden has a plan that acknowledges the work-related questions on the minds of many older Americans. That includes protecting former workers now dependent on social security, increasing benefits for workers who spent 30+ years working, and eliminating penalties for teachers and other public-sector workers. And for the growing number of people who are choosing to continue working as they age, Biden’s plan would push existing bipartisan legislation to improve age discrimination protections, as well as expand the earned income tax credit (EITC) to be available to workers over the age of 65.

Despite being in office for almost four years, the president—a mere three weeks before voting ends to choose the next occupant of the White House—has yet to unveil a substantive plan for older Americans. His latest claim is that Medicare recipients will receive, prior to November 3, a $200 card for use for prescription drugs. But there’s no evidence of what program would administer such an effort, whether a president even has the authority to make it happen, or how to pay for a plan that experts suggest would cost $6.6 billion. There’s a bit more to glean from his time in the White House, but the story is one of many proposed budgets that specifically include cuts to programs that benefit older Americans. Other efforts have lacked substance, including a May 2020 proclamation on “Older Americans Month,” which came near the peak of COVID-related deaths in the United States, a country where more than a quarter of people who have died from the coronavirus were nursing home residents.

The story of the last four years has been one of budget proposals that make cuts to programs that benefit older Americans.

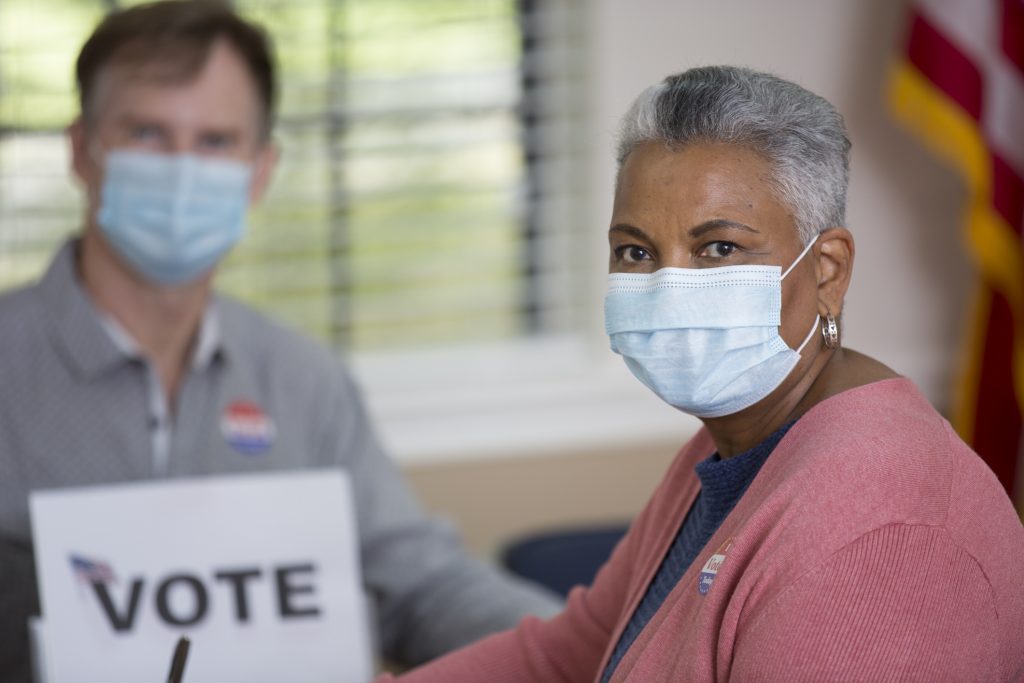

While we wait with baited breath to see how the election breaks across demographics, the most pressing issue over the next three weeks is ensuring that there’s a safe way for everyone—including older Americans—to be able to safely and securely vote with the assurance that their ballot, and the overall election outcome, will be counted fairly. Groups like AARP have released voting guides to help steer older Americans through an election with more variables than ever, while many are intent on voting in person while doing their best to minimize risks.

It’s not a consideration that our older Americans should have to make, and it’s one of a number of avoidable situations that we find ourselves in due to a widespread mismanagement of the response to COVID-19. But it does mean that as older people head to the polls in the coming weeks, masks on their faces and six feet between them and their fellow voters, there has never been a clearer set of choices as to the importance and the significance of leadership in the face of crisis. It matters for everyone, but perhaps most of all, older people in this country have borne the brunt of the past seven months while possessing among the greatest opportunities to chart the way forward.

The importance and significance of leadership in the face of crisis matters for everyone, but perhaps most of all, for the older people in this country.